For centuries the western world has viewed China as the sleeping giant of the east. In Caesar’s time, caravans routinely traveled west from the Chinese Han Empire, carrying goods, stories, and culture to the Romans, Egyptians, Greeks, and the Middle East. In fact many historians consider Ancient China the most advanced civilization of the world during the West’s middle ages. With the advent of the industrial revolution, however, China fell behind the West and is only now beginning to wake up.

In recent news China is preparing to enter the World Trade Organization through agreements signed with the U.S. At the same time, China has stepped up its war of words against the “renegade province” of Taiwan. Law-makers now face one question. Do the economic benefits of China’s entry into the WTO outweigh the dangers of an expanding China in the international arena. Those in favor of China’s acceptance into the WTO assume that economic freedom brings political freedom and reform. Many political leaders of both parties in the U.S. also assume that China’s economy will remain agriculturally dependent and below the other western powers. Both assumptions are flawed.

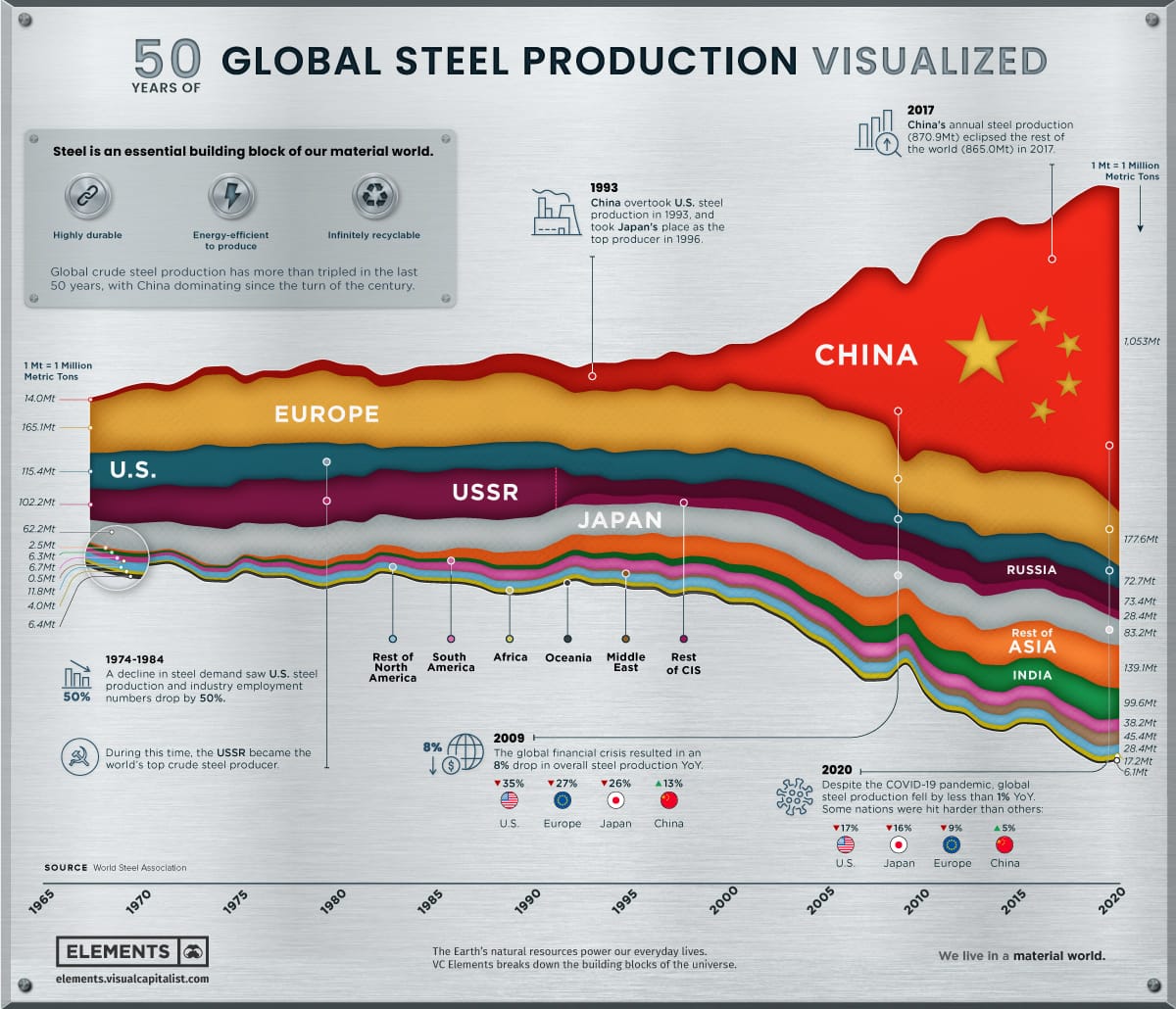

China’s economy is currently expanding quickly despite several challenges. Over the last 10 years China’s annual growth in GDP has averaged 8.5% versus the US’ 3.8% China’s current GNP is roughly one-seventh of the United States’. For the present time this disparity is reassuring, however, history has illustrated that Great Powers rise and fall based on their rate of economic growth relative to other powers. It is estimated that if China’s economy grows near the same rate it has for the last decade, it’s economy will surpass the United States’ by the mid twenty-first century. The most major economic problems facing China, are its massive population, its population’s continued growth, and how to feed this population. These problems are largely overstated however. For population growth to present a problem, it must out pace the growth of food production. In China, food production has easily exceeded population growth. As of 1999 China produced 490,000,000 metric tons of food. This represents a 2.3% annual increase in the amount of food produced from 1998. Population over the last 10 years has only grown 1%. For the last decade, food production has increased 3.2% annually if Fish catches are included. Clearly then, China is meeting domestic demand for food. In fact, it is doing so well that it is one of the leading exporters of corn and rice in the world.

All is not about food production, however, China’s overproduction of agricultural products has lowered the price of crops on the market and led to the mass underemployment of farmers and a growing migration to the cities. This mass migration has been absorbed by growing jobs in urban industries. The shift in population from the farms to the cities—in addition to the aging of China’s population, the decrease in fertility rates, and the growing share of industrial production in GDP—represents a clear signal that China is industrializing in the same ways that Western Countries have. This is an ominous sign. All is not well with the semi-conscious giant however. With the Asian Crisis of the late nineties, domestic overproduction, and corruption in state-owned-enterprises, the growth of China’s GDP has decreased from 12.6% to 7.8% from 1994 to 1998. This slow down is expected to be even worse for 1999-2000. This downturn has caused China to be more dependent on domestic demand as foreign investment has shrunk. China’s desire to enter the WTO is driven by this emerging problem. To maintain investment, production and economic growth, China desires foreign investment and competition. Chinese leaders believe that this investment will help rid domestic industries and state-owned-enterprises of corruption and will make many parts of the economy more productive and improve the quality of output. Western leaders believe that while this economic reform process occurs, a political reform process will also take place. This détente will—it is believed—create a friendship between the U.S. and China and will liberate the Chinese.

History does not support the contention that China’s economic transformation will be accompanied by a political transformation nor the contention that economic ties and trade forestall conflict. China has an almost un-broken tradition of autocratic and elitist political rule for over 2000 years. As one prominent Chinese historian pointed out,

Now that the United States is top nation in succession to eighteenth-century France and nineteenth-century Britain, historical perspective is more necessary than ever. In China the United States’ democratic market economy faces the last communist dictatorship, yet behind Chinese communism lies the world’s longest tradition of successful autocracy,. . . which call[s] into question the appropriateness of the American model [democracy] for China’s modern transformation.

In addition to China’s history of autocracy, History has many examples just in the last century of Great Powers going to war with their trading partners. Great Britain, France, Germany, the United States, the Dutch, and Japan all formed the largest group of trading partners in the world during the 20s and 30s despite the depression and tariffs. The Soviet Union and the United States formed many economic ties during the WWII, but that did not stop the Cold War.

Given these factors, opening trade with China while beneficial in the short run, could prove dangerous to the United States’ future security. With investment fueling further growth, it is highly possible that China could develop a massive economy powered by a huge working force. It is also not certain that this economic growth would be accompanied by an expansion of liberty. The existence of a fully industrialized autocratic China annexing Taiwan and other islands in the South China sea could make life for Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, and the U.S. rather painful. Already, the U.S. is experiencing a bolder China. This is due to the perception that the U.S. is appeasing China to reap the economic benefits. Ever since 1971 when relations with China were normalized and China replaced Taiwan on the UN security council, China has moved toward becoming a world power. It has struggled for 13 years to gain permanent trading status in the WTO to further its economic and political desires. Recently China has purchased several ships from the Russian Navy armed with tactical nuclear missiles that no U.S. Carrier Battle Group in the Straights of Taiwan could defend against. China has fought border wars with India, Russia, and Vietnam in the last 30 years. In 1995, China occupied several of the Spratley Islands in the South China Sea in an attempt to gain control of Asian shipping lanes. In 1996 China staged military exercises off Taiwan to influence Taiwan elections and discourage any move toward independence. Recently, China has repeated these threats and threatened war should the U.S. intervene. The U.S. cannot continue to appease and fund these actions. U.S. policy must seek to prevent China’s further acquisition of technology. The U.S. must follow policies that will prevent China’s economy from overtaking the United States’ and promote internal democratic reforms. The U.S. did not win the Cold War by trading technology and appeasing the Soviet Union. The U.S. won by containing Soviet Expansion and out performing it’s economy.

- 1. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstracts of the United States: The National Date Book (Washington, D.C., 1999), 641.

- 2. Ibid.

- 3. Paul Kennedy, Preparing for the Twenty-first century (New York: Vintage Press, 1993), 165-192 passim.

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. Statistical Abstracts of the United States, 857-858.

- 6. Ibid., 832-834.

- 7. Ibid., 832.

- 8. Ibid.

- 9. Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (New York: Vintage Press, 1987), 151-158 passim. & Preparing for the Twentieth Century, 35-39 passim.

- 10. “China’s Economy“, The U.S.-China Business Council, [articles on-line] 04 March 1999, accessed 15 March 2000, available from http://www.uschina.org/press/econmay99chops.html

- 11. Ibid.

- 12. “China signs trade deal with US, paving the way for entry into WTO”, Dow Jones.com, [articles on line] 15 November 1999, accessed 15 Mar 2000, available from https://dowjones.wsj.com

- 13. John K. Fairbank and Merle Goldman, China: A New History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 1. Fairbank was Francis Lee Higginson Professor of History at Harvard University and director of the East Asian Research Center at Harvard. Goldman is Professor of Chinese History at Boston University.

- 14. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, 302-314 passim.

- 15. Edward Timberlake & William C. Triplett, Red Dragon Rising: Communist China’s Military Threat to America (Washington D.C.:Regnery, 1999), 166-167.

- 16. Ibid.,61-64.

- 17. Ibid., 141. The Spratlys are a strategic island chain sitting in the middle of vital shipping lanes to Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, and offering access to developing oil fields in the South China Sea.