For our sake and for those still to be born, we should support the presidential candidate and the legislators who are making the tough, realistic decisions about the budget.

Two disturbing and seemingly unrelated discoveries recently jarred my view of America’s attempt to balance its federal budget. The first discovery came when, in one day, I bounced a check and got an outstanding Visa bill in the mail. The second discovery came as I watched the circus of reform attempts in the former Soviet countries.

My jarring concerns? First, there may be a sobering relationship between personal debt and national debt, and second, there may also be a relationship between our budget reform efforts and the roller coaster ride of Soviet reform. The connection? Our personal lack of budget discipline could lead us to follow the fickle route of reform being played out in former Soviet countries.

Although I have joined in the public outcry against the out-of-control spending in the nation’s capital — and believe Congress should live within its budget the same way private citizens do — my recent financial shock provoked a difficult glance in the mirror. What I saw there was my unbalanced personal budget and a lifestyle subsidized by credit. Worse still is the fact that I am typical of many Americans.

According to Ginger Applegarth, author of The Money Diet, only half of Americans set and maintain a personal budget. A significant segment of the population maintains its lifestyle by taking on substantial debt. In fact, last year, Americans spent over $38 billion on credit card interest alone. Ironically, Americans are increasingly troubled by the realization that their children will not be better off financially than they are, yet they resist making the lifestyle and spending adjustments necessary to improve the situation. Advertising pressure and market forces exacerbate the problem by discouraging savings and encouraging greater debt. Applegarth stresses that when the times change, our expectations, knowledge, and patterns of spending and saving must change as well.(1)

And times, they are a-changin’. During the era of big government, America had great intentions of providing for its citizens. In its ambitious attempts to build a “great society,” the national government injected a rapid flow of federal funds into a host of new programs. Most notably, the safety nets of Social Security and Medicare were widely cast. That was then. Today, current projections indicate that Social Security will begin drying up in 2019 and that the Medicare trust fund will run out as early as 2002.(2) As we compare the astronomical bill for great society legislation with its underwhelming report card of achievements, we are keenly aware that solutions to problems are not directly related to the volume of tax dollars thrown at them.

Despite the ugly crescendo that came with the government shutdown, 1995 was the year that saw the need for a balanced budget take political center stage. The landmark shift came as leaders on both sides of Pennsylvania Avenue agreed that the question was not whether the budget should be balanced but how. Finally, Congress was willing to tip some sacred cows and to present a more accurate picture of the budget problem. Seemingly motivated by an angry electorate, President Clinton amplified the sentiment of Congress when, in his State of the Union address, he announced, “the era of big government is over.” For those words to come from a Democrat — the Democrat who pushed for nationalized health care and the largest tax increase in our country’s history — we know that times have indeed changed. Now the expectations, knowledge and patterns of spending in Washington must change as well.

The Republican Party’s model for change has as its centerpiece, slowing the growth of federal spending. Without slowing the current momentum of government growth, radical cuts will inevitably burden future generations. Although the President and Newt Gingrich disagree over the best model for change, they agree on the need for change. Now is the time to re-evaluate the goals of federal programs as well as our dependence on public funds for services.

Much-needed change will be difficult, however, if we are not re-evaluating our personal budgets. If we continue to spend compulsively, we will lose our moral authority to demand more of our representatives who are themselves tempted to vote for pet programs, without assessing need or fiscal accountability. As consumers dependent on credit cards, how can we restrain a legislative body that similarly raises debt ceilings, raises taxes, and mortgages our future by simply overcharging on their voting cards? As we amass long-term debt in exchange for short-term gratification, our indictment of representatives who fail to cut long-term debt, in exchange for re-election, is self-condemning.

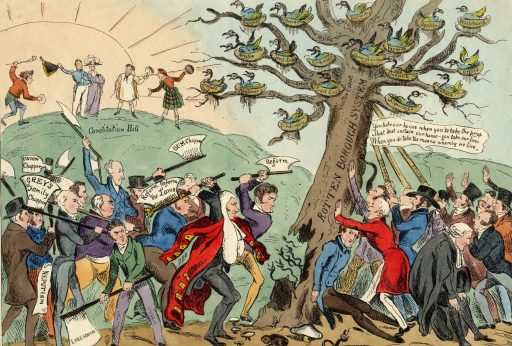

Ultimately driven by the election cycle, Congress proved unwilling to make hard choices, bringing the budget reform process to a grinding halt. With the onset of the election season, American voters have once again been called on for direction. As we head to the polls in November, weíve been trusted to determine the outcome of the budget reform drama. We have been asked, in effect, to either renew the Contract With America or provide an alternative mandate to guide our uncertain legislators. More importantly, we are going to elect the man who will sign or reject the final product. Will we be able to show the resolve our representatives lack as we face an opportunity to direct the debate? Clouding our decision will be all the politicians shifting into demagoguery. We can expect many to go back to their districts and defend federal programs on their popular merits without justifying their costs in the overall budget. Some political analysts predict that the backlash against the Gingrich budget reforms may result in voters kicking out large numbers of the representatives they elected to office in 1994. Before we do that, however, maybe we should examine the consequences of fickle reform efforts in the former Soviet countries.

In the early 90’s, member countries of the former Soviet Union elected reformers to invigorate their economies. Many reformers went beyond the modest attempts of glasnost and perestroika and recommended strong medicine for converting outdated socialist systems. When the consequential short-term growing pains began, the electorate demanded relief instead of enduring the discomfort necessary for the long-term rebound. Tragically, in almost every liberated Soviet country, communists were voted back into office in the preceding elections by promising the voters a “third way.” They offered to provide the economic stimulus of a free market and the security of socialist re-distribution. Once they were back in power, the communists stymied reforms and left the countries in disastrous states of limbo. (Only the Czech Republic was willing to wade out the transitional turbulence and now it fares the best of all the former Soviet countries.)

Many old-school tax and spenders are campaigning for an “American third way.” They promise yesterday’s securities without the painful sacrifices suggested by the reformers. The similarity is sobering. Will America vote out the belt-tightening reformers and embrace watered-down revisions? Granted, there are many details yet to be sorted out in the current budget debates, but we cannot retreat from the challenge that has already been partially accepted. For our sake and for those still to be born, we should support the presidential candidate and the legislators who are making the tough, realistic decisions about the budget.

Ultimately, our support will be a reflection of our personal budget priorities. After making some drastic budget changes of my own, I saw some improvement. But growing tired of the spending resolutions I had made, I started to use my credit card again. Then I stopped and wondered — will my lack of commitment on a personal level be mirrored by a citizenry who, with the first glimmer of recovery, or pang of negative side effects, gives up the medicine — the only thing able to cure the disease?

by Stephen Watters